Ancient and veteran oaks and natural capital

There are more veteran and ancient oaks in England than the rest of Europe. Currently 115 ancient oaks are recorded in England and only 97 elsewhere in Europe (including Ireland, Scotland and Wales). An ancient oak has a girth of greater than nine metres.

There are more veteran and ancient oaks in England than the rest of Europe. Currently 115 ancient oaks are recorded in England and only 97 elsewhere in Europe (including Ireland, Scotland and Wales). An ancient oak has a girth of greater than nine metres.

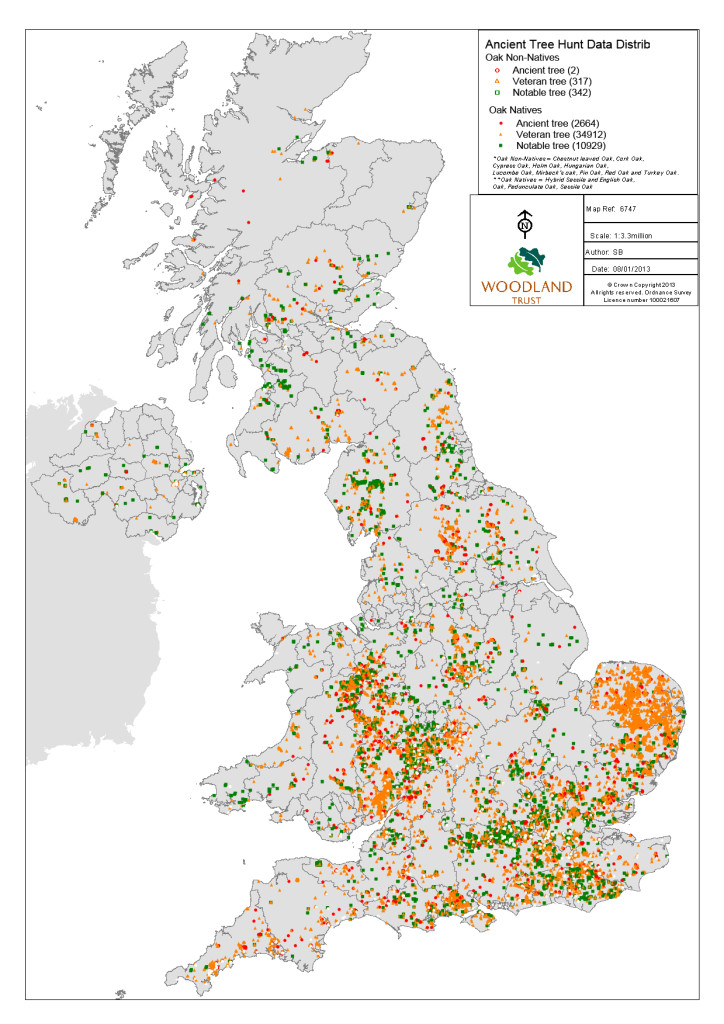

All this according to Aljos Farjon, the authority on conifer trees, for whom this is a major current study of broadleaved oak trees. He has plotted records of all veterans and ancient oaks (Quercus robur and Quercus petraea) in the country. Veteran oaks are those over six metre girth, and in total he has recorded 3,012 veteran and ancient oaks in England. Elsewhere in Europe there are concentrations in Sweden and Romania.

He is investigating the reasons for their survival in England, and not elsewhere and one of the major reasons is the absence of large scale forestry in England. Forest conifer plantings shade out old oaks and eventually kill them. And large scale royal and state forests began later in the UK than elsewhere, and so in Germany and France there were royal forest plantings from the sixteenth century. While in the UK the Forestry Commission was set up in 1919, following the Great War.

But why England, well one reason is the establishment of Royal Forests by the invading Normans as royal hunting grounds. Soon entire counties such as Essex became royal forests. 7.3% of ancient oaks survive in Royal Forests. The original Royal Forests were not wooded by the way, but signified deer. Forest laws were designed to protect venison and vert, notably red and then the introduced fallow deer and also wild boar and the green undergrowth or moorland which were their food. So Royal Hunting Forests need have no trees at all, e.g. Dartmoor, while many of the lowland forests had open savanna-like grassland or parkland like Richmond Park, Oliver Rackham termed this wood-pasture.

The oaks grew naturally and were not planted, and were protected from felling by the forest laws. But most were pollarded because the forest laws permitted that (but not coppicing). Similar were the chases created by nobles and they determined similar laws: 4.6% of the ancient oaks are associated with chases such as Sherwood Forest. Then there are medieval deer parks, in 1086 there were 40 deer parks and by 1485 there were 3000. And so 34.6% of ancient oaks are in former medieval deer parks as shown in Leonard Cantor’s Gazetteer of Medieval Deer Parks (1983). There are also Tudor deer parks (founded 1485-1601) which host a further 13%. Farjon also identified common land which supports 6.5% of surviving ancient trees. Finally there is ancient pasture landscape without deer herds and these form19.6% of surviving ancient oaks. Incidentally coppiced trees are excluded from Farjon’s survey, given the uncertainties of accurate measurement. But one overall conclusion is that it is the continuity of private land ownership which has ensured the longevity of these tree.

Aging trees is not accurate, The Woodland Trust tree age ready reakoner gives 9m girth as 900 years and 6mm as 400 years, but other ready reckoners give figures out by hundreds of years. And typically these large oaks are hollow, because the dead heartwood rots and so tree rings cannot be counted.

Everyone knows that oak support large numbers of insects, but the figures Farjon gave were astounding, Keith Alexander, who is contributing a chapter on invertebrates to Farjon’s book, reckons 7000 invertebrate species can live on one ancient oak.

Threats to ancient oaks include overshading by conifers, deep ploughing within the crown of the tree spread, fire and vandalism and horses rubbing their shows against the tree.

However, what is remarkable in England is the lack of protection. In Sweden and Germany such trees are protected, as natural monuments (naturminne in Sweden and Naturdenkmalen in Germany ). Could it be that the English are blasé about the real value of ancient and veteran oaks, given we have more of them compared with other European countries? Farjon argues for SSSI status for individual ancient trees. Landscape architects should lobby for UNESCO natural monument status for Britain’s ancient and veteran trees.

Dr Aljos Farjon FLS FRGS is working on a book on the subject with colleagues and lectured on the subject at the Linnean Society of London on Thursday 18 February 2016.

Refs.

http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/ancientoaksofengland

http://info.sjc.ox.ac.uk/forests/index.html

Leonard Cantor, Forests, Chases, Parks, and Warrens: 1983