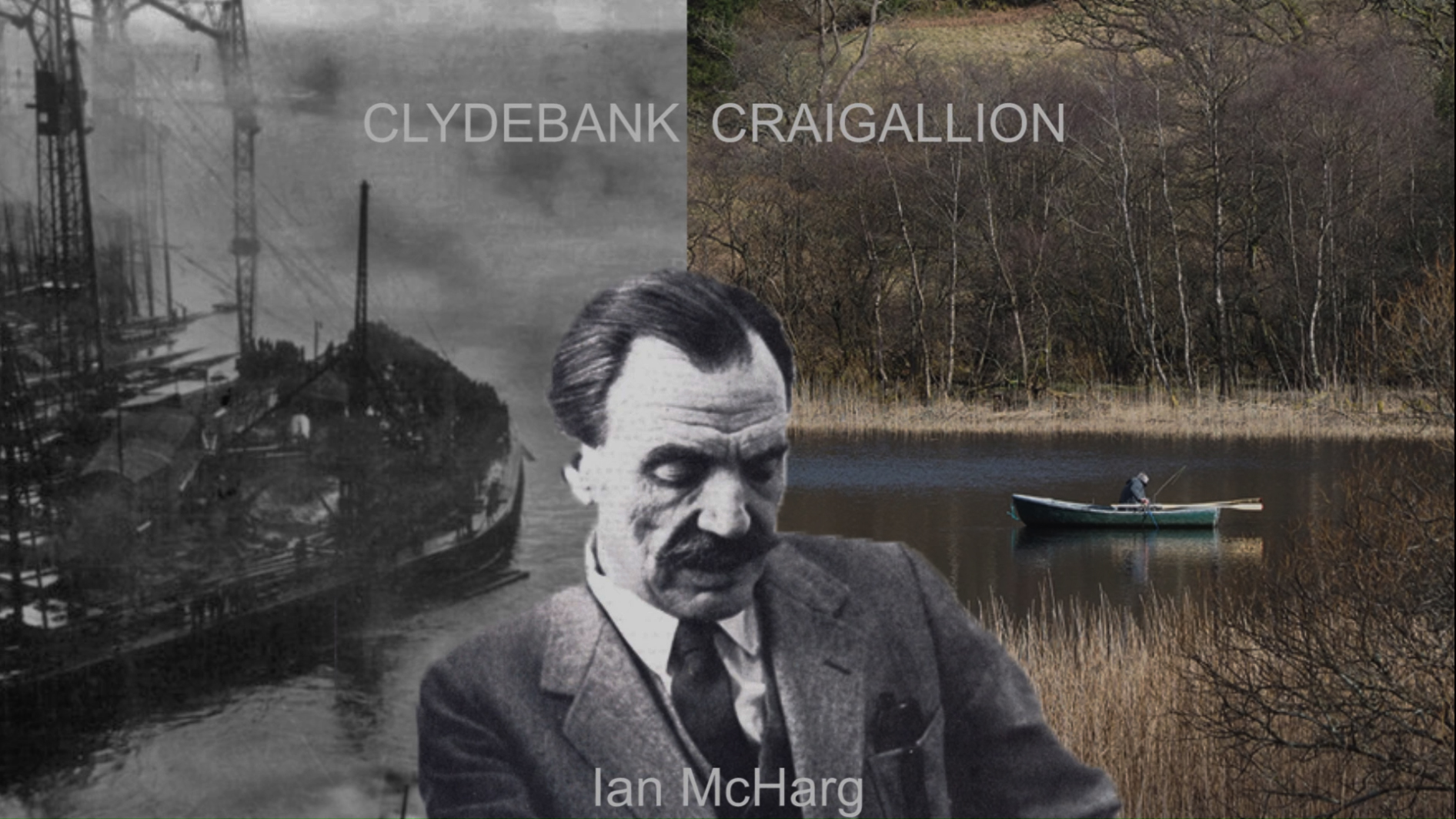

Ian McHarg’s boyhood in Glasgow, Clydebank and Craigallian Loch

Ian McHarg was born on Clydeside and became the most famous landscape architect of the 20th century. The importance of Clydebank in the development of his Design with Nature philosophy is explained in McHarg’s last book: A Quest for Life: An Autobiography by Ian L. McHarg

Two Billy Conolly jokes characterise Clydeside: ‘Before you judge a man, walk a mile in his shoes. After that who cares? He’s a mile away and you’ve got his shoes’. ‘The great thing about Glasgow is that if there’s a nuclear attack it’ll look exactly the same afterwards’. But McHarg soon saw the contrast between the inhumanity of Clydebank and the humanity of Craigallian Loch, leading to his interest in religion and to his passionate advocacy of Design with Nature. Like Bob Grieve, McHarg was one of the Craigallian Fire Men: ‘These men and boys have walked or cycled here from the city or Clydebank in search of fresh air, freedom and radical talk, and this fire is to become famous. It was the alma mater of people who changed Scotland’s attitude to the outdoors – writers and talkers, planners, outdoor educators, mountaineers and the founders of renowned climbing clubs.’ They also helped change America’s attitude to nature and the outdoors.

In Glasgow, McHarg is perhaps best remembered for his contribution to ‘making the outdoors great’. As discussed in the video, they should also remember and apply his Design with nature approach to landscape architecture. If they had listened to him in the 1940s, McHarg might not have left Scotland and Glasgow might be miles and miles better than it is today. Regarding the Fire Men, the Sunday Herald reported in 2012 that:

The year is 1932 and a camp fire is heaped high in the woods beside a loch 10 miles north of Glasgow.

Hanging above it on blackened ironwork is a large can labelled Rodine Rat Poison.

Around the flames perhaps 20 figures huddle, their faces reddened and shadowed. Their clothes are patched and layered – it is May and the nights are cold.

Some have schoolboy crops, some can’t afford a barber. All are lean, most are young. Those with blankets draw them closer. Others use the “travelling man’s duvet”, scrunched-up newspaper stuffed down their jackets. They dip tin mugs in the can to draw out tea, the poison long since rinsed away. One starts to sing – Home On The Range, the popular cowboy tune – and a harmonica joins in. Later they will sleep in the open, on the ground, near the fire.

These men and boys have walked or cycled here from the city or Clydebank in search of fresh air, freedom and radical talk, and this fire is to become famous. It was the alma mater of people who changed Scotland’s attitude to the outdoors – writers and talkers, planners, outdoor educators, mountaineers and the founders of renowned climbing clubs.

Those who knew it said it was always burning, day and night, the dubious tea can boiling. It became known simply as the fire that never went out. Now, more than 70 years after the last embers cooled at the fire by Craigallian Loch, on the West Highland Way at Carbeth, a permanent marker is to be placed there.

The names of a handful of “fire-sitters” are known, including Jock Nimlin, an influential climber, National Trust For Scotland stalwart and journalist who wrote about the fire and its Rodine kettle. It is thanks to his journalism, and the autobiography of climber and broadcaster Tom Weir, that we know men from the fire undertook long and difficult journeys across hills and glens, mostly on foot, to get to the mountains and crags they loved

Some stories come from men such as Iain and Willie Grieve, passed down by their fire-sitter father Bob, later Sir Robert. They say the sitters were central to the outdoors movement that defied landowners and opened up the countryside to ordinary people, like a Caledonian wild west, and were even involved in the occasional gunfight with gamekeepers. Scott Valentine, a climber from Bearsden, says his grandfather Tom was one of the Craigallian weekenders. “He spoke fondly of his experiences around the fire,” Valentine says. “He would pass by en route to the hills and take a brew while enjoying the craic or debating the pros of Socialism, Clydesider style.”

But we can only guess who most of the men were, when the fire began, and when and why it ended. If any of the original sitters are still alive, they will be in their 90s or older. So far none has contacted the Grieve brothers through their Craigallian Fire memorial website. We look as though through the smoke of the fire itself at a past just beyond our grasp.

It is thought the fire lasted from the late 1920s to perhaps the mid-to-late 1930s. Most of Bob Grieve’s companions were industrial workers or jobless, and the talk was of Socialism and Communism. Grieve and others said many of the Scots who fought on the Republican Government’s side in the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939 had been fire-sitters.

The rest may have included at any time Nimlin, Weir and other early members of the tough, notorious Creagh Dhu Mountaineering Club – Johnnie Harvey, who in 1932 founded its Glasgow rival, the Lomond MC; Ian McHarg, later an influential professor of town planning in the United States; and Grieve’s friend, Malcolm Finlayson, who would become a police chief superintendent and shoot murderer James Griffiths in 1969, after the gunman went on a deadly rampage in Glasgow.

Bob Grieve, who died in 1995, went on to become a civil engineer, the first professor of planning at Glasgow University and chairman of the Highlands And Islands Development Board, but he always remembered the fire. “He had a humble upbringing in Maryhill, one of six children in a family that hovered on the edge of dire poverty,” says his son Willie, 62, when we meet at the site to briefly relight the fire. “But the fire was hugely significant for him because it was here and around here that he met the people who developed his ideas and made him who he was.”

The Grieves have raised £5000 for a stone memorial on the site, including a substantial donation from the John Muir Trust. The stone base is in place and a grand unveiling is planned next month.

The choice of site is obvious enough. It’s a hard evening or morning’s walk from Glasgow and Clydebank. It has a burn, was sheltered by woods and city people already used the area: the Carbeth huts holiday homes sprang up about the same time.

The fire was, of course, part of the movement of Glaswegians into the hills and woods around the city in the years after the First World War, a movement reflected in other cities in Scotland. In his biography of Nimlin, IDS Thomson says expanding public transport, more private cars and lorries to “tap” lifts from and mass-produced bicycles were key to the movement, inspired by walking columnists such as Tramp Royal in the Evening Times and Hobnailer in the Daily Record.

Historian and hillwalker Richard Oram of Stirling University traces the roots of the movement to the outdoors image of the Victorian royal family and upper classes. “There was an image of the superior physical state of the ruling class,” he says, “and a lot of this was based on their involvement in outdoor activities. People expected the Victorian gentlemen to be able to walk for miles, with high-status people going on huge tours.

“Poets like Wordsworth and Byron would walk more than 20 miles a day across rough country, and this was seen as a demonstration of their physical advancement.”

Oram believes such ideals filtered down, and churches helped pass them to the “lower orders” in part to prevent working men with time and money on their hands spending both in pubs.

He also says the First World War had a profound effect on men who would have been the older fire-sitters. In the army, large groups were cooped up with time to talk and a sense of ill-treatment: ideas of social justice would find fertile ground.

Former seaman and engineering industry worker Lawrie Travers is 91 years old and until recently still stepped out in the Campsie Fells. He has also kept busy working as a volunteer on the tall ship Glenlee at the Riverside Museum in Glasgow. Originally from Partick, he took to the hills in his teens when the Craigallian blaze still shot sparks to the heavens.

He agrees cheap public transport was an influence. “It was a 2d [2p] tram ride to Milngavie, or you could get the bus out to Blanefield, and then you had the freedom of the open country,” he recalls.

And although Oram says churches pushed people into the outdoors, Travers suggests that, by the 1920s, with greater social freedom, more people would cock a snook at religious convention and instead take to the open air on their day off.

So, as the athletic ideal of the upper classes filtered down, it met rebellion and ideas of social justice in the men around the fire. “They would have asked themselves why these healthy and exciting outdoor pursuits should be reserved for the elite,” says Oram.

With no money for long-distance trains, expensive boots, thick tweed or accommodation, and unable to negotiate access to private estates – as gentlemen climbers could – getting into the mountains would have been tough.

But a fire like Craigallian, warm enough to keep the night chill at bay, where people would talk of defying landowners and reclaiming the land, would have been a starting point.

From the fire, the Southern Highlands were within walking range. Glen Coe was a hitch-hiking target. Some isolated cottages welcomed visitors, letting them sleep in byres and stables – Travers recalls one winter night in a stable when the heat from horses below was a welcome bonus.

But there were conflicts, too, when estate workers would prohibit men heading for the mountains. On one occasion, when Nimlin planned to camp on a property, he was met by obstructive estate workers. He kept going all night until they were too exhausted to follow him, then lit his fire.

Willie and Ian Grieve believe returning Spanish Civil War veterans brought a new edge to things: their father said many kept their weapons, and an exchange of shots with gamekeepers was not unknown. Thomson records a rifle kept by Creagh Dhu members at a bothy near Glencoe, and Creagh Dhu old timers tell me it is probably still buried there.

Travers has his own recollection of guns in the hills in the 1950s, when he was the organiser of the Lomond club bus. Creagh Dhu members were allowed to fill empty seats. On one occasion they shot a hind and stashed the meat on the parcel rack.

“A woman came to me and said she had blood on her clothes, and it had come from above. I wondered what on earth was going on,” he recalls. “I didn’t know I was running a bus for the shooting club.”

They called it the fire that never went out but eventually it did – for ever. No-one is quite sure why. The owners of the site at the time have no descendants and it has changed hands twice since the 1930s and its end some time after 1935 has several possible explanations.

Tom Weir’s friend, fire-sitter, Lenzie butcher and ornithologist Matt Forrester wrote that the sheer popularity of hillwalking was to blame. “With the enthusiasm came the camp followers, the litter louts and despoilers,” he wrote.

“The fire was banned. The land proprietor forbade it under penalty of law. For a while the notice board was disregarded. A few hard cases persisted with the fire, but its day was done -“

Others ascribe the end to the loss of men to Spain in 1936, but at least one younger sitter, Ian McHarg, recalled veterans at the fire talking about the civil war, dating its end to perhaps 1938. Nimlin wrote of an attempt, probably in the 1940s, to revive the fire. The police were called, two men were taken to court, and although one – in true rebel style – called the magistrate a “tinpot Mussolini”, there were no more revivals.

But in a metaphorical sense – and it always was a metaphor for something greater – the fire lit in the 1920s is still burning. Grieve, Nimlin and Weir influenced everything from climbing ethics to national park policy.

The Lomond Mountaineering Club, started by fire-sitter Johnnie Harvey in 1932, is still home to the spirit of good companionship, individualism and readiness for a good argument, as is the Creagh Dhu. There is also a link between the fire-sitters and modern Munro-bagging. It took off when Hamish Brown published his magical account of the game, Hamish’s Mountain Walk, in which he made the first non-stop trip around the 279 hills – as the list stood at the time – higher than 3000ft in Scotland.

Munro’s table of mountains over 3000ft was published in 1891, and in the 77 years before Brown’s book, 200 people climbed them all. Seven years after the book, that number had doubled. Now there are 4000-plus people who have climbed all the Munros.

Brown, now in his 70s and living in Fife, knew many fire-sitters, and as a young man lived the same rugged life of dossing and tramping the hills, inspired by them. “It was the ethos of people like Tom Weir,” he says. “We didn’t have the gear in those days. The spirit of going out and roughing it was very strong. After talking to them you didn’t have any doubts about sleeping in haystacks and under bridges.

“I believe the tougher the introduction people have to the outdoor world, the more likely they are to stay interested.”

Those fire-sitters, with their newspaper bedding and rat poison kettle, their tussles with gamekeepers and marathon walks, had the toughest of introductions. And perhaps that’s why their passion for the hills lives on.‘