Humphry Repton, public goods and the landscape architecture of golf

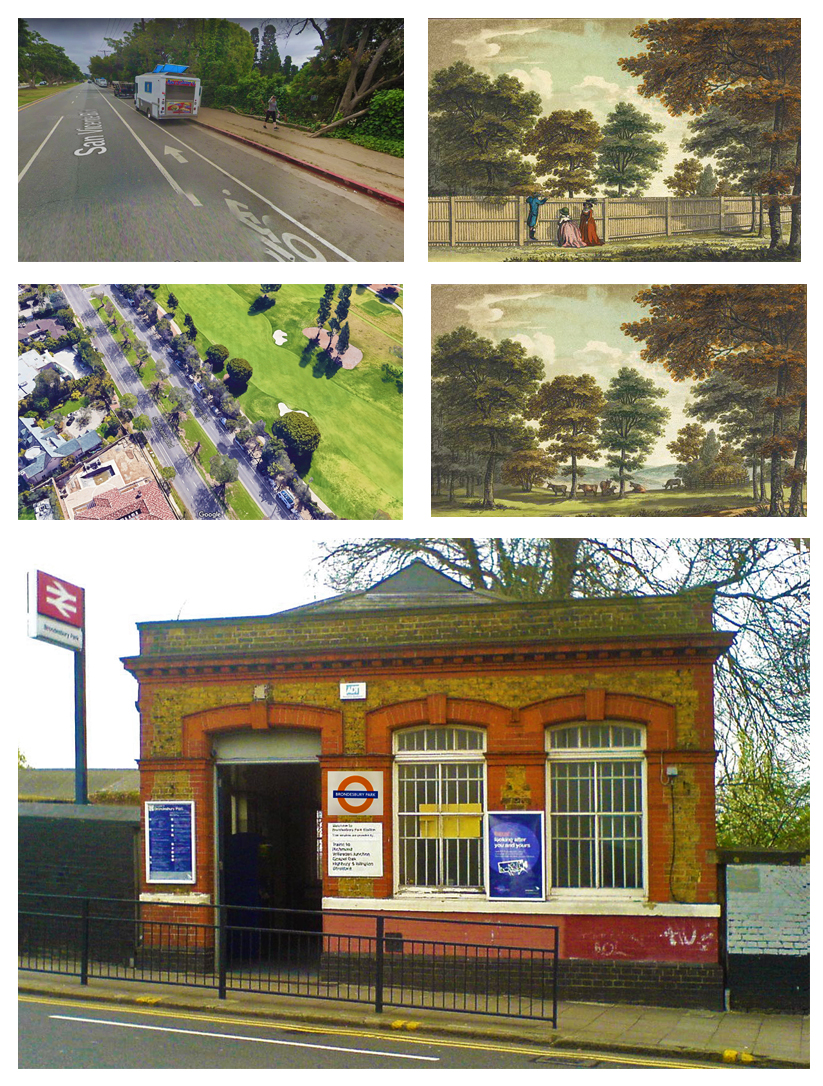

Repton, who was by far the most important landscape architecture theorist of the nineteenth century, used images (left, above) to make the case for opening the view of Brondesbury Park to the public.

Malcolm Gladwell, in a Revisionist History podcast on A good walk spoiled, makes the same point about the luxurious Brentwood Country Club in Los Angeles. He says the club gets gargantuan tax breaks but provides no public goods in return. Walkers and joggers suffer from the traffic and the chain link fencing. His podcast, once you get past the ads, is powerfully argued. My only point of disagreement is with his view that golf courses are beautiful. Very few are and they most are anti-ecological.

Repton’s support for public goods was followed by John Claudius Loudon’s advocacy of public parks (in which Los Angeles is also deficient) and of the term ‘landscape architecture’. Gilbert Laing Meason, who devised the term in 1828, argued for public goods and quoted a letter from a geologist (John MacCulloch) to a poet (Sir Walter Scott):

The public at large has a claim over the architecture of a country. It is common property, inasmuch as it involves the national taste and character: and no man has a right to pass himself and his own barbarous inventions as a national taste, and to hand down to posterity, his own ignorance and disgrace, to be a satire and a libel on the knowledge and taste of his age. Against this, we have all an interest in entering our protests; and thus, for the present, ends the explosion of my architectural anger. Do, my dear Scott, put yourself in a passion for once, like Archilochus, and write some Iambics against these people.

The podcast, I’m pleased to say, has a contribution from a landscape architect.