Jordan Peterson: God, post-Postmodernism and Metamodernism

Is Jordan Peterson’s philosophical position Modern, Postmodern, post-Postmodern or Metamodern?

Politically, the left castigates Jordan Peterson as ‘right-wing’ and even ‘alt-right’1. Sections of the right do admire him. But Peterson sees himself, reasonably in my view , as a classical liberal’2. His intellectual position is best described as post-Postmodern. When a student, he espoused religious scepticism, socialism and scientific Modernism. Today, he is a scientist who holds that religious beliefs have a central place in our psyches and in the conduct of our lives. Since he accepts Modernism and goes beyond it, one could see his position as ‘Postmodern’ without an extra ‘post-‘. But there are reasons for not applying this label (1) Postmodernism connotes ‘skepticism, irony, or rejection toward what it describes as the grand narratives and ideologies associated with modernism’ (2) since Peterson defines his own position in steadfast opposition to Postmodernism, he is likely to reject the classification, just as he would not want to be described as post-Nazi or post-communist or post-something else. ‘Metamodern’ is an alternative, discussed below.

Jordan Peterson’s religious beliefs

Peterson might agree that the argument of his 1999 book (Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief 3) positions his views after modernism. And his use of the word ‘belief’ highlights a key difference from the religious scepticism that grew, with the scientific method, from Enlightenment rationalism4. It caused Ruskin to lament, in 1851, that ‘if only the Geologists would let me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.’5 Then Nietzche proclaimed, in 1882, that ‘God is dead’6 and Richard Dawkins wrote, in a book on The God delusion7 that ‘To succumb to the God Temptation in either of these guises, biological or cosmological, is an act of intellectual capitulation’8. Peterson and Dawkins both turned against Christianity in their teens, for scientific reasons, but Peterson has turned back.

Peterson might agree that the argument of his 1999 book (Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief 3) positions his views after modernism. And his use of the word ‘belief’ highlights a key difference from the religious scepticism that grew, with the scientific method, from Enlightenment rationalism4. It caused Ruskin to lament, in 1851, that ‘if only the Geologists would let me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.’5 Then Nietzche proclaimed, in 1882, that ‘God is dead’6 and Richard Dawkins wrote, in a book on The God delusion7 that ‘To succumb to the God Temptation in either of these guises, biological or cosmological, is an act of intellectual capitulation’8. Peterson and Dawkins both turned against Christianity in their teens, for scientific reasons, but Peterson has turned back.

The Wikipedia entry on post-postmodernism notes that :

Consensus on what constitutes an era can not be easily achieved while that era is still in its early stages. However, a common theme of current attempts to define post-postmodernism is emerging as one where faith, trust, dialogue, performance, and sincerity can work to transcend postmodern irony.

Peterson was raised in a Catholic family and relates that when a young man ‘I asked the minister, at one point, how he reconciled the story of Genesis with the creation theories of modern science. He had not undertaken such a reconciliation; furthermore, he seemed more convinced, in his heart, of the evolutionary viewpoint’9. Peterson therefore abandoned his childhood faith. But he is now sympathetic to religious faiths and persuaded of their importance to acting in the world. As well as Christianity, he references other faiths: Mesopotamian, Jewish, Greek, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist and more. In a 2019 interview about his beliefs, Peterson’s answers included the statements that:

- ‘To speak the truth and act it out, that’s what it means to believe.’

- ‘Unless you act it out you should be careful about claiming it.’

- ‘And so I’ve never been comfortable saying anything other than I try to act as if God

exists.’

These answers are good evidence of Peterson having an intellectual position which, as the Wikipedia article on post-postmodernism phrased it, rests on ‘faith, trust, dialogue, performance, and sincerity’10.

Metamodernism

Jeffrey Nealon, in a book on Post-Postmodernism, acknowledges that the term is ‘just plain ugly; it’s infelicitous, difficult both to read and to say, as well as nonsensically redundant’. Yet he goes on to explain that ‘For my purposes, the least mellifluous part of the word (the stammering ‘post-post’) is the thing that most strongly recommends it’11. I agree, though the abbreviation PoPoMo is more chummy.

Jeffrey Nealon, in a book on Post-Postmodernism, acknowledges that the term is ‘just plain ugly; it’s infelicitous, difficult both to read and to say, as well as nonsensically redundant’. Yet he goes on to explain that ‘For my purposes, the least mellifluous part of the word (the stammering ‘post-post’) is the thing that most strongly recommends it’11. I agree, though the abbreviation PoPoMo is more chummy.

Some of the alternatives to post-postmodernism were collected by Alison Gibbons for an article in the Times Literary Supplement. Its title was ‘Postmodernism is dead. What comes next?’ She wrote that:

There are many terms for this new supplanting cultural logic, this shift in the ruling belief system: to name a few – altermodernism, cosmodernism, digimodernism, metamodernism, performatism, post-digital, post-humanism, and the clunky post-postmodernism.’

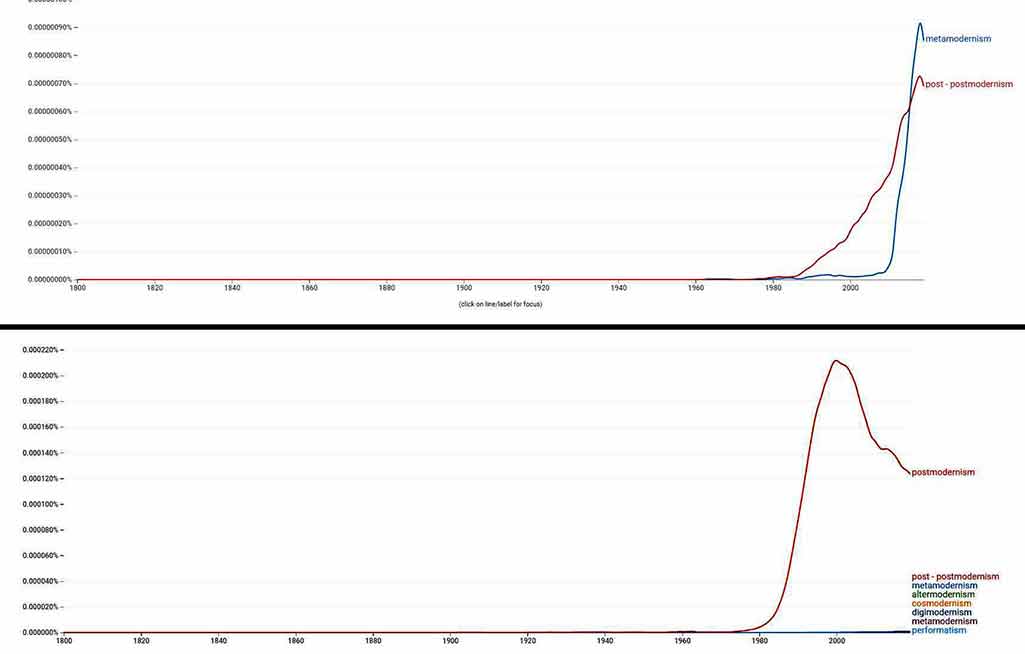

From this list my second choice would be ‘metamodernism’ and the Google Ngram, indicates that it has a 2020 lead over ‘post-postmodern’, with the declining trajectory of ‘postmodernism’ showing that it could be overtaken by either of the newer terms.

The first use of metamodern was by Mas’ud Zavarzadeh, in 1975. He saw recent fiction as moving ’within the framework of a comprehensive private metaphysics, towards a

The first use of metamodern was by Mas’ud Zavarzadeh, in 1975. He saw recent fiction as moving ’within the framework of a comprehensive private metaphysics, towards a

metamodern narrative’12. The kinship of ‘metamodern’ with ‘metaphysics’ is appealing (to me) and the term is well-supported, and promoted, in a 2017 book with the title Metamodernism Historicity, Affect, and Depth after Postmodernism. Seeking to periodise the 2000s, the authors point to a range of aesthetic phenomena which are ‘characterised by an attempt to incorporate postmodern stylistic and formal conventions while moving beyond them’, and adding that ‘for us, this language is metamodernism. There, we’ve said it.’ 13

My reservation about metamodernism is that, though the authors of the book see it primarily as a ‘language’, its adoption as the name for a period could happen and would depend on another period name, Modernism. And this term is beyond its use-by date. Surely, cultural historians cannot long persist in their use of ‘Modern’ for a period which began before 1900. It’s ridiculous. So for me the built-in absurdity of ‘post-postmodern’ is an attraction. It dramatises the need for historians of art and culture to settle on a new set of period names, remembering, of course, that a lot of water had to flow under a lot of bridges before Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical and Romantic gained the relatively settled status they now enjoy14. Another problem with ‘Metamodern’ could be that it accepts too much of Postmodernism’s cynical political baggage. For the present, I think ‘post-postmodern’ is a good name for a group of ‘after-modern’ and ‘after-postmodern’ cultural trends.

Peterson, narrative, myth and design theory

For garden history, which is what I have written most about, my 2013 suggestions for periodising garden design in the twentieth century were: Arts and Crafts Style, Abstract

Style, and Post-Abstract Style. I included a diagram for ‘sustainable gardens’ but didn’t call it the ‘Sustainable Style’. Then, in 2019, I suggested ‘Belief Style’ as an alternative15. ‘Style’ is not a popular term with designers but design historians can scarcely avoid its use. A style is something which you can see when you look back but which should not guide the creative process.

Instead of mentioning styles, as their eighteenth and nineteenth century predecessors would have done, current designers tend to overuse the personal pronoun. They say ‘I want…’, ’I like…’ and ‘I’m going to…’. And when they do this, my thought is ‘Come on folks. It’s not about you. It’s about the site, about the times you live in, and about your clients’. If the designers are students, I might then recommend Roland Barthes essay on ‘The Death of the Author’16.

The aspect of Peterson’s work of most interest to designers is his treatment of narrative and myth17. Ninian Smart, an analyst of faith traditions, saw mythology as one of the seven dimensions of religion but he writes of ‘a widely shared sense that myths are dead, mere curiosities of the past, and that the truly modern person has rid himself of symbolic forms, except in the arts, where they are carefully kept in a ghetto’. Modernists tend to see themselves as ‘author-gods’.

Peterson uses the Ten Commandments as examples of ‘myths’ which ‘we still act out… although we can no longer justify our actions’18. He sees science as a way of understanding the material world and myth as a way of understanding subjective worlds. The Commandments are psychological ‘maps’ which are useful for worldly action, just as cartographic maps are useful for finding your way from A to B. They show where you are and, like design drawings, where you want to get to. Peterson’s own Twelve rules for life became an international bestseller and a Youtube sensation19. Though appealing, especially to young men, they are idiosyncratic and lack the tested, timeless authority of The Ten Commandments.

In his approach to myth, Peterson was inspired, like Geoffrey Jellicoe, by Carl Gustav Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious. An interest in the structure and meaning of myth is also associated with Mircea Eliade (who Peterson admires), and with Sir James George Frazer, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Vladimir Propp and many others. Their work led to the structuralist’ ambition ‘to uncover the structures that underlie all the things that humans do, think, perceive, and feel.’20 Peterson summarises his argument in this way:

The world can be validly construed as a forum for action, as well as a place of things. We describe the world as a place of things, using the formal methods of science. The techniques of narrative, however – myth, literature, and drama – portray the world as a forum for action. The two forms of representation have been unnecessarily set at odds, because we have

not yet formed a clear picture of their respective domains. The domain of the former is the “objective world” – what is, from the perspective of intersubjective perception. The domain of the latter is “the world of value” – what is and what should be, from the perspective of emotion and action.21

Designers, like clinical psychologists, engage with the world both as ‘a place of things’ and as ‘a forum for action’. They must analyse and understand the often invisible physical and biological ‘structures’ which underlie the individuality of places (the genius loci). Then

they must recommend courses of action. It’s a complex task which can gain much from ‘the techniques of narrative’. They are of value in developing and explaining concepts – and in persuading clients of their worth. Geoffrey Jellicoe was a master of this craft, and the three volumes of his Studies in landscape design 22 are, for this reason, the most significant of his books, and the twentieth century’s best examples of how to develop and explain sophisticated landscape architecture proposals.

With his design for the Kennedy Memorial at Runnymede, Jellicoe developed a particular interest in ‘the invisible world’ (I’ve tried to explain this in a Youtube video). For him it was the world of ideas. For the design approach known as landscape urbanism, it is more to do with the landscape structuralism: geology, ecology, hydrology, climatology and so forth23.

In 1994, I classified Jellicoe’s design approach as ‘postmodern’24. Later, having read more about postmodernism and critical theory, this was modified and I wrote in a blog post that ‘You could see it as a progression from Renaissance to Modern to Postmodern. Or, like me, you can take the view that [Jellicoe’s] approach was always postmodern: using the term in the sense given it by Canon Bernard Iddings Bell. One could take the same view of TS Eliot’s poetry. It was forward-looking and modern while also traditional. As Winston Churchill said in 1944:”I confess myself to be a great admirer of tradition. The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward” (often misquoted, rather well, as ‘the farther backward you can look, the farther forward you can see’).’ Jordan Peterson uses this principle.

In his 1926 book, Postmodernism and Other Essays, Iddings Bell argued that religious fundamentalism is unacceptable, because of the advance of science, and that a full Modernism is also unacceptable, because science only takes you so far. Equating Modernism with the Liberal theology of George Tyrrell and Alfred Loisey, Iddings Bell put forward a Postmodernism which welcomed the insights of science but held firm to the core principles of Christianity. Here are some quotations25:

- The Bible can no longer be regarded as an inerrant touchstone, the wholly infallible gift of the Eternal to struggling man.(p.4)

- Modernism is, properly, a way of looking at religion which originated with Loisey and Tyrrell, two eminent and deposed Roman Catholic priests. (p.7) [Both were

excommunicated] - There is no art for art’s sake. All art exists for the sake of Truth. (p.13)

- The scientific intelligentsia now realizes, and for the most part freely admits that, merely by scientific methods, nothing of basic importance, of primary

importance, of ontological importance, can be discovered. (p.21) - Fundamentalism is hopelessly outdated. Modernism has ceased to be modern. We are ready for some sort of postmodernism. (p.54)

- Insofar as he exists at this moment, the Post-modernist is apt to be a man without a Church. Protestantism, Modernism, and Romanticism alike seem to him to miss

the point. (p.65)

Peterson and Jellicoe can be placed in Bell’s category of ‘men without a church’. They respect modern science and they respect the myths which have guided humans throughout the ages.26 My great aunt, who lived through the religious debates of the early twentieth century, would have classified their beliefs as ‘something somewhere’. I classify them as post-postmodern.

Inspired by Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life, I will end with two conclusions, which might be described as 2 Rules for Design which involve myth and allegory (1) urban and landscape designers should use what Peterson calls Maps of Meaning (2) we should all adopt Jellicoe’s narrative approach and to developing and explaining design proposals. This is what I attempted for the Druk White Lotus School, which will be the subject of a future podcast.

Notes and references

1 A film on The Rise of Jordan Peterson provides ‘an intimate portrait depicting the rise to fame of beloved and reviled best-selling author and professor Jordan Peterson’ and a review by Quilette sees the film as ‘particularly notable’ because ‘

it neither shies away from the political controversies surrounding Peterson, nor allows itself to be defined or limited by them.’ Peterson is very popular on Youtube. The mainstream media acknowledges him as a ‘leading public intellectual’ but, particularly from the left of centre, he is much criticised (eg by Vox Haaretz and the Guardian). David Brooks, began an opinion piece the New York Times by writing that ‘My friend Tyler Cowen argues that Jordan Peterson is the most influential public intellectual in the Western world right now, and he has a point’.

2 Peterson explained this stance Youtube Jan 28, 2018

3 Peterson, J., Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief Routledge 1999

4 Daniel Fusco has urged the church to embrace post-postmodernism but, to my surprise, found a greater enthusiasm for its predecessor. He wrote that ‘Modern evangelicalism is obsessed with postmodernism. There are books being written by the thousands on the subject. A recent search of an online website for a major Christian bookstore revealed almost six hundred titles with the word postmodern in it.’ (Fusco, D., Ahead of the Curve: Preparing the Church for Post-Postmodernism Tate Publishing, 2011 p.14) The main influence of pos

5 Ruskin, J., Works 36:115 Letter to Henry Acland, 24 May 1851

6 Nietzche, F., The Gay Science 1882 (Dover Edition, 2006 p.81)

7 William Reville criticised Dawkins in the Irish Times (Thursday 16th January 2014) arguing that ‘Philosophers must oppose arrogance of scientism’. See also: Wikipedia entry on scientism.

8 Dawkins, R., The God Delusion 10th Anniversary Edition Penguin 2006 p.12

9 Peterson, J., Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief Routledge 1999 p.xi

10 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-postmodernism (accessed 12.10.2020)

11 Nealon, J., Post-Postmodernism: or, The Cultural Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism Stanford University Press 2012 p.ix

12 Zavarzadeh, M. (1975). The Apocalyptic Fact and the Eclipse of Fiction in Recent American Prose Narratives. Journal of American Studies, 9(1), 69-83

13 van den Akker, R., (Editor), Gibbons, A. (Editor), Vermeulen, T. (Editor), Metamodernism Historicity, Affect, and Depth after Postmodernism (Radical Cultural Studies) Rowman and Littlefield International Ltd., 2017 p.3

14 Stephen Knudsen, in a brilliantly written and illustrated article, expresses a preference for metamodernism to ‘the hideous term post-postmodernism, let’s pray that it is simply a place marker’. ( ‘Beyond postmodernism. Putting a face on metamodernism without the easy clichés’, Artpulse Magazine 2013)

15 See Youtube video The Belief Style of garden design published 12th October Oct 12, 2019

16 Barthes, R., Image music text Fontana 1977 p.142ff

17 I have written more about story patterns in Chapter 3 of Turner, T., City as landscape, Spons, 1996. ‘In the days when stories were passed on by word of mouth, from generation to generation, details became blurred and

structural patterns were laid bare. Vladimir Propp initiated the structural analysis of wonder tales, or fairy tales, which others have taken up. An amazing worldwide uniformity has been found in such tales. Their themes are hope and tragedy. Paradise is lost and paradise is found again. Cinderella is a classic example. She lived in paradise until her mother died. Then came trials, tribulations, mysterious happenings and, eventually, a happy ending’ (p.31) This chapter is also available as an illustrated Youtube video with the title Landscape Architecture Ideas: design process and as an unillustrated podcast.

18 In Maps of meaning (p.19) Peterson writes that ‘The great forces of empiricism and rationality and the great technique of experiment have killed myth, and it cannot be resurrected – or so it seems. We still act out the precepts of our forebears, however, although we can no longer justify our actions. Our behavior is shaped (at least in the ideal) by the same mythic rules – thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not covet – that guided our ancestors, for the thousands of years they lived, without benefit of formal empirical thought… If myths are mere superstitious proto-theories, why did they work? Why were they remembered?’

19 Peterson, J.B., 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos Penguin 2019

20 Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structuralism accessed 12th October 2020,

21 Peterson, J., Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief Routledge 1999 p.xxi

22 Jellicoe, G.A., Studies in landscape design, Oxford University Press Vol 1 1960, Vol 2 1966, Vol 3 1970.

23 It would be interesting to know how landscape urbanism theorists, like Charles Waldheim and James Corner, classify their views: Modern? Postmodern? Metamodern? Post-postmodern? Please ask them if you have the opportunity.

24 Turner, T., British gardens: history, philosophy and design Routledge 2013, p.389

25 The page references in brackets are to: Bell, I.B., Postmodernism And Other Essays Morehouse Publishing Co. 1926

26 Ninian Smart, grouped the ‘Narrative and Mythic’ dimensions of religion as ‘stories (often regarded as revealed) that work on several levels. Sometimes narratives fit together into a fairly complete and systematic interpretation of the universe and human’s place in it’. His approach to comparative religion is described as phenomenological. With regard to his own beliefs, Smart told an interviewer that ‘I often say that I’m a Buddhist-Episcopalian. I say that partly to annoy people…. I like to annoy people who think that a religion can contain the whole truth. No religion, it seems to me, contains the whole truth. I think it’s mad to think that there is nothing to learn from other traditions and civilizations. If you accept that other religions have something to offer and you learn from them, that is what you become: a Buddhist-Episcopalian or a Hindu-Muslim or whatever.’ I have not come across a reference to Smart by Peterson but it seems likely that he is familiar with Smart’s work.