Who conceptualised the landscape architecture profession before its foundation?

John Claudius Loudon was the pioneer

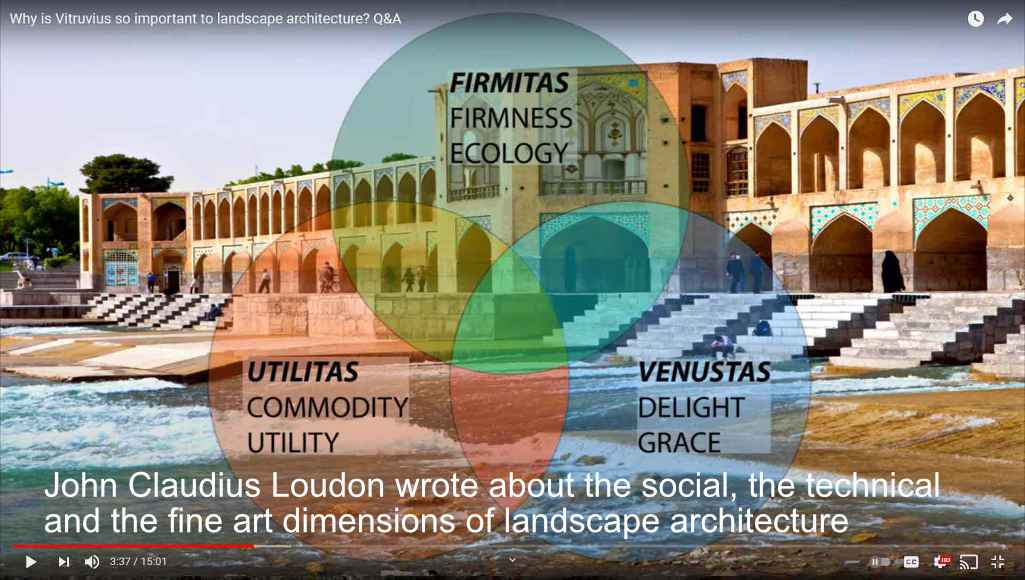

Without Loudon, the landscape architecture profession would not have its current name or its current social, technical and artistic focus. These characteristics can be analysed as follows:

The social dimension of landscape architecture

Socially, Loudon had a passion for serving the public and for the creation of what are now called ‘public goods’. Paul Samuelson, a famous economist, defined them as non-rivalrous non-consumable. Loudon’s belief in their importance came from his presbyterian ancestors. As set out in The Claudians (my fictionalised biography of John Claudius Loudon and his cousin Claudius Buchanan) the most important influence was their shared grandfather Claude Somers, also known as Claudius Somers. He was active in the Cambuslang Awakening (a famous 1742 religious revival in the Scottish village of Cambuslang, where their mothers were born. Claude Somers is known to us through the life and writings of Claudius Buchanan. This is why it is a dual biography of Loudon and Buchanan.

The technical scope of landscape architecture

Technically, Loudon’s idea was that the skills that go into making ‘landscape gardens’ are relevant to the wider landscape, beyond garden walls and estate boundaries. Loudon applied them to greenbelts (which he called ‘breathing zones’) to greenways (which he called ‘promenades’), to urban design, to planning agricultural landscapes, to highway planning to transport planning and to much else.

The fine art dimension of landscape architecture

Artistically, Loudon drew on what Christopher Hussey called The Picturesque. This was an approach to garden and estate design and planning that developed in the eighteenth century. Its famous leaders include William Kent, Lancelot Brown, Humphry Repton, Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight. As a young man, Loudon believed he could be the first to put the ideas of Price and Knight into practice. In his maturity Loudon reasoned that The Picturesque was not enough. So he launched The Gardenesque in 1832. At the outset, it was a style of planting design that used exotic species to make designs ‘recognisable’ as works of art that could not be mistaken for wild natural scenery. Loudon was much influenced by the Romantic Movement and, looking to the romance of history, published the first illustrated systematic history of the art of garden design.

The landscape architecture profession’s name

The term ‘landscape architecture’ was invented by Gilbert Laing Meason, a fellow-Scot and a friend of Loudon’s. But only 100 copies of Meason’s book on The Landscape Architecture of the Great Paintings of Italy (1828) were printed and, but for Loudon, it would surely have been lost. The two men would have ‘edited’ (in the sense of ‘written’) a book together had Meason not died in Venice. The term survived and was taken up by Downing, Olmsted and Vaux only because Loudon used it (without explanation) in his edition of the collected works of Humphry Repton.

The development of landscape architecture as an organised profession

From the standpoint of what is now a worldwide profession, the most important sentence in Meason’s book is the comment that ‘Our parks may be beautiful, our mansions faultless in design, but nothing is more rare than to see the two properly connected.‘ There is a chain of conceptual links between this and the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) account that ‘Landscape Architects plan, design and manage natural and built environments, applying aesthetic and scientific principles to address ecological sustainability, quality and health of landscapes, collective memory, heritage and culture, and territorial justice. By leading and coordinating other disciplines, landscape architects deal with the interactions between natural and cultural ecosystems, such as adaptation and mitigation related to climate change and the stability of ecosystems, socio-economic improvements, and community health and welfare to create places that anticipate social and economic well-being.’ The links flow through J.C. Loudon, F, L. Olmsted, P. Geddes, N. Newton, G.A. Jellicoe, and I. McHarg.

For more information about the conceptual chain please see the Q&A section on the Landscape Architecture Association website. It links to a set of videos and web pages that explain the history. theory, aims, objectives and methds of landscape architects and landscape architecture.

See also: Loudon and the development of landscape architecture.