East Central London Cycle Network: reviews, transport planning and landscape architecture

For most of the past half-century London’s cycle transport planners have had their heads in the sand. Instead of looking for desire lines which link origins to destinations, as other transport planners do, they have looked for underused ‘quiet’ roads and for underused space on busy roads. They don’t seem to have realised that the usual reason for roads being underused is that they go from nowhere to nowhere. Painting white bikes on the road and putting up blue and white road signs cannot make indirect routes through housing estates popular with cyclists. Commuting by bike is not the outdoor equivalent of a session on a fitness bike in a gym. It can be a heavenly experience or a hellish experience. Too often, it is a purgatory experience. We ride in fear. List of 18 London cycling posts and videos.

Transport planners and landscape architects should together work to create a cycle network which is functional and enjoyable. The Embankment section of East-West Superhighway 3 has both these qualities. I could spend a happy day riding back and forth between Westminster Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge. But it is only a good quality urban landscape because of what was there before TfL built the excellent cycle route. When combining use and beauty in a cycle route is impractical, as in Upper Thames Street, then:

- For journeys to work, to school, to the station, to the shops and to other destinations, cyclists need routes which are as short and as safe as possible. Directness is much more important for cyclists than it is for motorists.

- For recreational journeys, estimated to be 35% of all trips, the pleasure is as much in the travelling as in the arriving. Cyclists want to experience fine streets, gardens, forests, rivers, lakes, beaches and the other visitor attractions in which London is so rich. I guess this applies even to people whose reason for cycling IS the outdoor equivalent of an exercise machine.

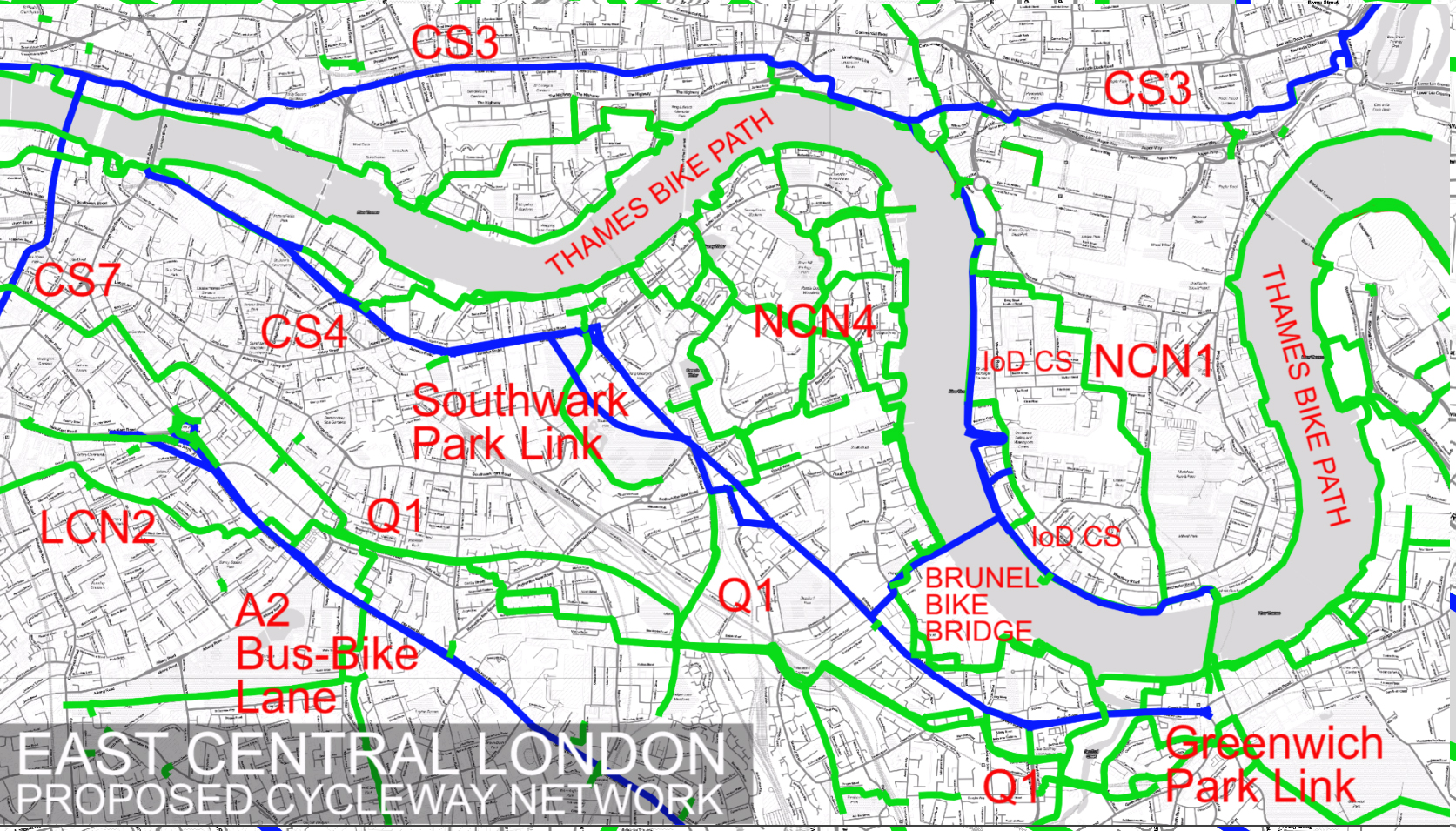

The map of designated cycle routes in South East London is superficially impressive (see post on cycle mapping). But the 2014 Government data showing how much of this exists as facilities on the ground tells a very different story. It’s like bits of branch without trees. It’s not a network.

The admired Netherlands CROW manual argues for a network that connects origins with destinations. This is very good. But we also need leisure routes.

- South of the Thames, East Central London has signposted routes which are of little use for either leisure or commuting. Quietway 1, opened in 2016 is a compromise which makes a poor stab at both objectives. The area needs a Cycle Superhighway on the A200, as is promised, and the Thames Path needs to be adapted for cycling.

- North of the Thames, East Central London’s cycle planning is much better. CS3 is a good, fast, A to B connection and a key component in East London’s cycle infrastructure. Though it could be safer and more of a pleasure to ride. NCN13 is also good – but as a scenically attractive leisure route, planned for this purpose, by Sustrans, and largely segregated from motor vehicles.

- The Isle of Dogs could be transformed into a cyclists paradise, instead of a tangled wire pie without wire, by completing the Cycle Superhighway on its West Bank and making a leisure cycleway on its East Bank. The Isle could have London’s first Five Star Cycling Greenway.

Planners are catching up with the fact that cyclists are now a quarter of Central London’s commuter traffic. So they now need a five-year plan for doubling this figure. Like the money homeowners spend on insulation and double glazing, investment in cycle facilities produces long-term benefits – and without the ongoing costs of fuel, health-damaging air pollution or climate change. Planning for the bicycle has to become a fundamental aspect of urban landscape planning and design.

My experience as a London cycle commuter

After becoming a London commuter in 1973 I read about Cycle to Work Week (now Bike Week). The hour-long walk-and-train journey seemed un-cyclable but I decided to give it a go, riding from Wimbledon to Baker Street. Back in those days, the only kind of cycles were the ones you needed to pedal fast and strong. And phew, an hour of that can get exhausting! Fast-forward to the present – with the electric bike option, trails might not seem as grueling as before. There were few other cyclists, the traffic was terrible and the air choked me – but I loved it. The weather was beautiful and I’ve now been cycling in London for 45 years, in wind, sun, rain, snow, fog and floods.

My first experience of a signposted cycle route was in the early 80s. I was riding along the A2, as usual, and noticed a sign to what is now London Cycle Network Route 2. So I turned off, got lost 6 times, fell off my bike and ended up at the Elephant and Castle instead of Westminster Bridge. There was no cycling infrastructure at all and the route was longer, slower and more dangerous than riding on the A2. This absurd and tokenist approach to London cycle planning continued until the first of the 2015 cycle superhighways opened some 40 years later. After using many of the routes shown on the above map I revisited them and produced a set of videos:

The landscape architecture of cycleway planning and design

The video at the top of this post proposes a landscape approach to London cycleway planning and design. To make a good cycle network, engineers and landscape architects need to work together – just as engineers and architects need to work together to make good buildings. Individual routes are important. The aim is to plan and design a cycle network which is a joy to use and which takes cyclists from origins to destinations, including leisure destinations. It’s likely that:

- Some routes will have the primary role of taking commuters directly from A to B,

- Other routes will have the primary role of letting cyclists experience great urban landscapes

You can see the advantages of this approach by riding the Royal Cycle Loop in Central London. Amazingly, it now has both a high quality commuter cycle route and a high-quality leisure cycle route – some parts of which have to be walked because there are so many pedestrians.

London is in urgent need of cycling plan. It should connect origins to destinations, including leisure destinations, and the routes should be designed to get high scores on cycleway assessment methods, typically for: Safety, Directness, Coherence, Comfort and Attractiveness. London also needs better cycle maps – which tell the truth about their qualities. Maps of backstreets daubed with white bikes and blue signs are a waste of everybody’s time and money.

Bike Bridges and Skycycle Tubes

As London moves, slowly but surely, towards becoming a Great Cycling City, more imaginative investment projects will become feasible.

- Mayor Sadiq Khan has approved pedestrian and bicycle bridges for Nine Elms and and for Rotherhithe. This is good. But they were not planned in the context of a London cycle network plan and I believe Deptford would be a better location than Rotherhithe. It would give the bridge a significant place in East London’s cycling landscape.

- London’s first cycle tube could be built above London’s first railway track – the London & Greenwich Railway. The capital cost would be a fraction of providing equivalent capacity on trains and the running costs, year after year after year, would be negligible. Charmingly, and the air pushed forward by each cyclist in a one-way tube would help other cyclists going in the same direction. Oli Clark, a London landscape architect, did some great designs in 2014 and Norman Foster helped publicise them with the name Skycycle.

Cycle Route Maps

London cycle maps are better than its cycle network – but chaotic. The recommended solution is for public bodies and local councils to contribute data to the OpenStreetMap database.