Rewilding in Britain

Re-wilding Ideas of re-wilding have been around for some decades, indeed the concept under other labels has been around for upto a century, for instance, the project to back breed the Auroch. Indeed Heck cattle are an attempt dating back to the 1920s. The term was first coined by the US conservationist activist David Foreman in the 1980s.

Current enthusiasm for re-wilding in Europe began with the Dutch project in the 1980s to create a savanna grassland and wetlands on the last large polder to be reclaimed, Zuidelijke Flevoland. This became the 56km2 Oostvaarderplassen, and in 1989 just three decades after being reclaimed it was given Ramsar status.

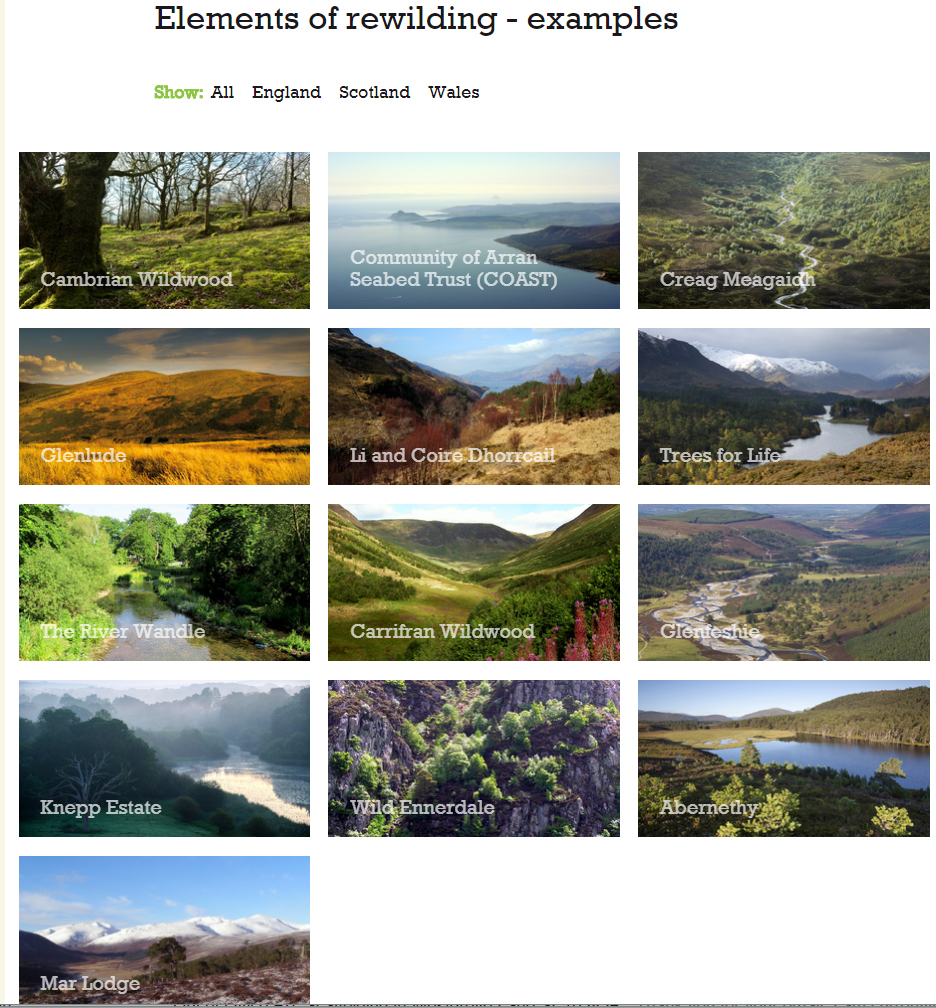

In Britain there are now a whole series of rewilding projects. They are of two types, either reintroducing a particular species, often an apex species but also including insect reintroductions such that in 1984 of the Large Blue Butterfly (Maculinea arion). The larvae initially feed on the flower-heads of Wild Thyme (Thymus polytrichus) but after three week they feed on Myrmica red ant grubs for the rest of their larval cycle.

But more typical are the reintroductions of predators, and large mammals, such the beaver following its reintroduction since 2009 in the Knapdale Forest in Agyle. There is also a small trial in Devon, on the River Otter, by the Devon Wildllife Trust. Then there is Scottish Wildcat Action efforts to counter hybridisation of this threatened species. Successful bird reintroductions include Red Kites often now seen on the M40 through the Chiltern, the Crane to the Lakenheath and Hickling, the Ospey to Rutland Water, to Wales, and the Lake District.

I am a huge fan of the Lake District and firmly believe that we should do everything in our power to preserve it. There are so many gorgeous hotels and other types of accommodation that would make the perfect spot for a Lake District honeymoon or vacation, and so reintroducing the wildlife and plants that make this such a beautiful part of the world is crucial.

Larger landscape re-wilding

However, larger landscape re-wilding projects in the UK involve whole stretches of countryside similar to the Dutch example. There are a number of wetland and marshland projects (e.g. The Great Fen, Cambridgeshore and Dingle Marshes in Sufflolk. So that they have become almost commonplace.

But more challenging are lowland agricultural landscapes such as the 1,400 ha Knepp Castle Estate West Sussex (which includes a Repton Park). The estate is heavy clay and formerly unprofitable dairy pasture and arable land, which since 2001 has been allowed to develop under the advice of ecologist Frans Vera (who was also involved in the Oostvaarderplassen). This has happened naturally under a grazing ecology with Tamworth pigs, English longhorn cattle, red and fallow deer, and Exmoor ponies. This has led to a whole series of species developments including plants, and invertebrates, birds and small mammals.

The Pumlumon Project, Ymddiriedolaeth Natur Maldwyn

A much larger project is that in mid-Wales, run by the Montgomery Wildlife Trust embracing 40,000 ha of the Cambrian Mountains around Plumlumon. Since 2007 the Trust has been pursuing the following aims:

Element 1 Carbon Storage

Peatlands are the UK’s biggest store of carbon. Like many upland areas, Pumlumon holds vast reserves of peat. In the 1950s and 60s, much of it was drained in a largely unsuccessful attempt to improve grazing, so releasing large amounts of stored carbon into the atmosphere. Hnee, reduce these emissions by blocking the drainage ditches. As the bogs become wet again the mosses start to grow, absorbing carbon each summer and locking it away as new peat. At the same time, the existing stores of peat are protected from further erosion, and species marginalised by the original drainage can return.

Element 2 Reconnecting Habitat

Climate change means plants and animals trapped in a fragmented landscape which need green corridors to migrate. Climate change may shift the natural range of some species northwards by more than 250km and/or nearly 300m higher in altitude. After ice ages, plants and animals migrated along natural corridors. But in today’s fragmented landscapes many species will be trapped in habitats which can no longer support them. Hence the needs to provide corridors linking lowland and upland habitat.

Element 3: Storing flood water

At least three million people depend on water which falls as rain in the Pumlumon Project area: the Severn and Wye headwaters are here.

Given the direct link between upland land management and the severity of lowland flooding; strategic tree planting, restoring hedgerows, fencing out watercourses and reducing stocking levels all help to increase the permeability of upland soils, reducing rapid run-off during heavy rain.

The Pumlumon Project area consists of more than 3,700ha of hydrologically active habitats, including wet heath, raised bog, blanket mire, valley mire, and wet woodland.

Element 4: Bringing back wildlife

Just some of the species benefitting from the Pumlumon Project include Ospeys, Red Grouse, Hen Harrier, Black Darter dragonflies and Round Leaved Sundew

Element 5: Changing grazing patterns

Ecologically sensitive grazing doesn’t just enhance the landscape and restore wildlife; it can be more profitable for farmers. Reduction of stocking densities and using cattle instead of sheep, at moderate intensities, and at the appropriate time of year can increase the range of plant species in the turf and the cattle hooves can help break up soil pans.

Element 6: Recreating habitats

Even where large areas of strategically important habitat have been lost, we can put them back. It just takes time The plan is to create a network of wetlands, woodland and species-rich grassland, connected by a latticework of rivers, streams, hedgerows and grass verges.

Element 7: Developing Green Tourism

Underpinning the Pumlumon Project is a simple expectation: a healthy, diverse, wildlife-rich landscape attracts visitors

Including walking, kayaking, mountain biking and wildlife watching. This widens the economy for the local community.

Element 8: Involving communities

The ultimate measure of success is whether local people share these aims and support this project. George Monbiot’s re-wilding writings have made him unpopular in mid-Wales because he directly attacked sheep farming which is a bastion of Welsh-speaking culture, you need to work with the community and support the community.

The IUCN World Database on Protected Areas reports 15% of the earth’s land area is protected. However, the E.O.Wilson, the father of sociobiology, argues 50% of our land area should be wilderness. Meanwhile we are losing wilderness areas.

Rewilding Britan now publish a newsletter with updates including details of rewinding scheme such as that at the Ken Hill Estate, Norfolk; for details:

https://www.rewildingbritain.org.uk

They include details of the Rewilding Network which aims to promote the practice:

https://rewildingbritain.frb.io/rewilding-network