The origins of landscape architecture a professional title and an art

I really enjoyed Charles Waldheim’s lecture, above, and it inspired me to reconsider our profession’s name. I plan to review Waldheim’s book on Landscape as Urbanism – a general theory when it appears and will comment here on the section of the lecture in which he discusses the term landscape architecture. In 1982 I attributed its origin to Gilbert Laing Meason (‘Scottish origins of landscape architecture’ Landscape Architecture May 1982 pp 52-55). Waldheim accept’s Joseph Disponzio‘s attribution to Morel, which was new to me. Disponzio wrote a PhD thesis on Morel and, taking a particular interest in where Olmsted’s term ‘landscape architect’ might have come from, has uncovered much useful evidence.

See: scottish_origins__of_landscape_architecture

The French term architecte-paysagiste is at least 24 years older than the British term ‘landscape architecture’, having been used in in the Almanach de Lyon in 1804 and in Morel’s obituary in 1810. It was not used in Morel’s Théorie des jardins, or his subesequent books, but other French designers used the term, including Louis-Sulpice Varé, when he was superintendent of the Bois de Boulougne. Olmsted visited the Bois in 1859 and met Varé’s successor, Adolphe Alphand, who may have mentioned the term architecte-paysagiste. An architecte-paysagiste was an architect who designed gardens in the English landscape style. Disponzio’s views are explained in this lecture

The British term ‘landscape architect’ was first used by Meason in 1828. It was welcomed by John Claudius Loudon and used in the title of his collected edition of Repton’s works. Andrew Jackson Downing, who greatly admired Loudon, used ‘Landscape or Rural Architecture’ in his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America. Olmsted refers to Humphry Repton and probably knew his work from Loudon’s edition, since the original books have always been scarce and expensive.

Disponzio comments on Meason that ‘The book had nothing to do with landscape architecture, but rather with the architecture in landscape paintings of Italy.‘ The second point is correct. The first point is incorrect: Meason’s focus, like that of the profession Olmsted founded, was on the relationship between buildings and settings. Meason wrote that:

In recommending to architects to study the picturesque effects of buildings, the site adapted for them, and those accompaniments of terraces, gardens, and other decorations, to set off their architectural designs, we are influenced by the desire to raise and extend the theory and the practice to what we consider belongs to the art. It was thus in Italy, when the fine arts were in perfection, in laying out great villas by artists who often combined the practice of painting and architecture; and until it be adopted in Britain, the designs of the architect never will have justice done to them in the execution. Our parks may be beautiful, our mansions faultless in design, but nothing is more rare than to see the two properly connected. We need not repeat the just remarks of Sir Uvedale Price on this subject. Let the architect, by study and observation, qualify himself to include in his art the decorations around the immediate site of the intended building, and the extended taste among the gentry of England will second him.

This paragraph could have a place in a founding charter for the landscape profession but does not constitute evidence for Olmsted having read Meason’s book or known of its existence. Meason also had a deep concern for the public interest – which became a distinguishing characteristic of the profession Olmsted founded. Quoting Macculloch, Meason wrote that:

The public at large has a claim over the architecture of a country. It is common property, inasmuch as it involves the national taste and character; and no man has a right to pass himself and his own barbarous inventions as a national taste, and to hand down to posterity his own ignorance and disgrace to be a satire and a libel on the knowledge and taste of his age.

[Macculloch, J. Highlands of Scotland, vol. i. p.359 the book is addressed to Sir Walter Scott]

Loudon used this quotation in his Architectural Magazine and elsewhere. Mark Laird is right that Loudon ‘anticipated most facets of an embryonic landscape architecture’.

Olmsted could have acquired the term ‘landscape architect’ from Morel or from Meason or from both or of them – or from Calvert Vaux or A.N.Other. Vaux, who met Downing in 1851, may well have known that William Andrews Nesfield described himself as a landscape architect when designing a garden for Queen Victoria (see biography of Nesfield and details of his garden designs). I hope new evidence will be found but it will not affect the definition of landscape architecture or its antiquity as a design profession. Meanwhile, the origins of landscape architecture are outlined in the below video:

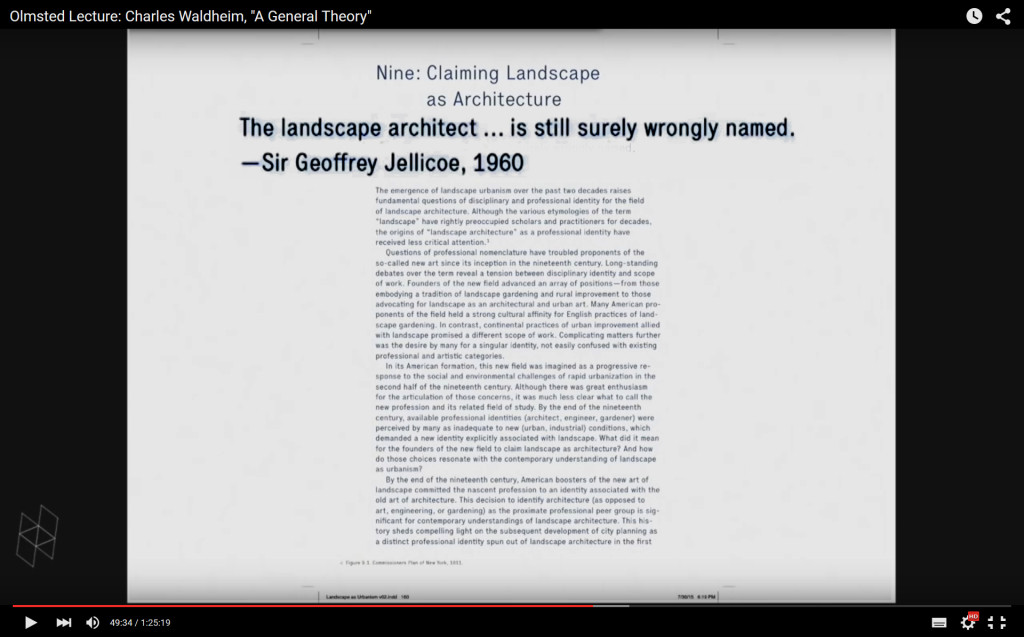

John Dixon Hunt, in an essay on ‘Early landscape architects who weren’t ”landscape architects”‘ reflects that ‘what we today call landscape architecture – was practiced without that title in the past’. After writing about Kent, Brown and Repton he notes that ‘if we push back further into the seventeenth century and even earlier, we encounter creators of “landscape architecture” who emerged from a whole cluster of professions, skills and trades’. Hunt believes that landscape architecture is ‘not a happy term, but it suffices, despite more recent attempts to coin phrases like landscape urbanism and even ecological urbanism as the appropriate terminology. As regards these recent re-nominations, it is, in the end, interesting to observe that “landscape urbanism” succeeded in dumping the term ‘architecture”, and then that ‘ecological urbanism’ also got rid of the term “landscape”, so that the two emphases on landscape and architect have simply disappeared’.

Charles Waldheim (from 49:34 in the video) dates the advent of landscape architecture from the start of the sixteenth century and makes a good case for Landscape as Urbanism – which is the title of his book (to be published by PUP in 2016). I view landscape and ecological urbanism as design methods, not as candidates for replacing ‘landscape architect’ as our professional title. Waldheim quotes Geoffrey Jellicoe who, writing as founding president of the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA), declared that: ‘The landscape architect… is still surely wrongly named’ (Crowe.S., ed Space for living, 1960).

I did not know of this comment before seeing Waldheim’s video but remember asking Geoffrey for his opinion of ‘landscape architect’ as a title. As I recall, Jellicoe’s reservation was about the word ‘architect’ which, he thought, over-emphasised our concern with geometry and under-stated our concern with biological processes. My question was probably put to him when writing an essay on landscape architecture and ‘The blood of philosopher kings’. The essay (available for download) includes an account of my concerns about the title ‘landscape architect’ and relates that : ‘I then spent some time trying to devise a better title for the landscape profession. My favoured proposal was “topist’ (one who makes places). But then my historical investigations resumed, now into the meaning of the word “landscape’. I found that it had dropped out of Middle English but had been re-introduced from Dutch in the sixteenth century, as a painters’ term, linked to the Ideal, Neoplatonic, theory of art. A “landscape’ was a special kind of place: an ideal place. The theory derives from Plato, who, believing the Form of The Good is the proper goal of human endeavour in life as in art, argued that philosopher kings are the people best suited to rule society. Plato’s Theory of Forms, or Ideas, led directly to the Neoplatonic axiom that “art should imitate nature’.’ Though my confidence about Olmsted borrowing the term from Meason has diminished somewhat, I have not changed my mind about the revitalisation of landscape theory and I have become optimistic for landscape urbanism as an approach to dealing with relationships between buildings and their surroundings. Landscape urbanism is, as a design method, applicable both at the large scale of city planning and the small scale of site planning.

As explained in the below video, I see the University of Greenwich landscape design for a Dragon Garden at a height of 3,500m in Ladakh as an example of a landscape urbanism design process. It integrates cultural layers (the extended mandala and other symbols from Buddhist culture) with functional layers (circulation, security etc) and with natural process layers (geology, soils, vegetation etc).